Reading the statement reminded me of the tools we had to rely on before the development of today’s academic resourcing models that I’ve been writing about in these blogs. The improvements are relevant for achieving the benefits described in the joint statement referenced above as well as my own Reengineering the University and forthcoming Resource Management for Colleges and Universities. I’d like to share some of my experience in the early days of higher education analytics to show just how big a change the current models portend, and why that change is so important.

Dawn of the Academic Analytics Era

The story begins in the 1970s when I moved from being a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business to the university’s central administration as Vice Provost for Research. Being an economist from the Business School, it wasn’t long before I was appointed to the committee charged with advising Provost Bill Miller on resource management (the Stanford Budget Group). Bill, a computer scientist, was an early advocate for analytics in higher education. His strong support of analytics transformed the work of the Budget Group, established Stanford as a leader in the field, and created a competence and culture of analytics that persists to this day.

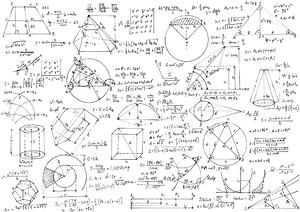

Planning Models for Colleges and Universities (my book with David S. P. Hopkins), which won the Operations Research Society of America’s Frederick W. Lanchester Prize, makes the case for planning models and describes then-current applications for topics in the outer ring of Figure 1, below. Comprehensive market information systems for higher education were not developed until the rise of the internet, but in general the earlier models were based on approaches that are readily recognizable today.

Academic Analytics Before Course-Based Models

Until about a decade ago, higher education’s analytic toolbox included no course-based representation of teaching activity. (Imagine Figure 1 without its core element.) The outer-ring models consider problems one at a time. Worse, they do not describe teaching activity, “the business of the business,” at the level of individual courses—which is how provosts, deans, and professors think about academic resourcing. David Hopkins and I recognized the problem in our chapter on production and cost models, but the technology was not far enough advanced to make course-based models possible.

Without course-based analytics, it was necessary to rely on the cost and revenue allocation models depicted at Figure 1’s two-o’clock position. Mostly they distributed the university’s overhead costs to departments and programs. Back in the 1960s, however, researchers at the University of Toronto and the University of California-Berkeley had tried to predict the resources needed for handling enrollment changes. (The models were called CAMPUS and RRPM, later known as the NCHEMS Resource Requirements Prediction Model.) This was the right question for budget-makers, but the models fell short of expectations.

RRPM represented teaching activity by a two-dimensional “Induced Course Load Matrix” (ICLM) that reported the total student credit hours produced by each department or departmental division (on the rows of the matrix) to support each of the institution’s degree programs (on the columns). The data, which did not distinguish among individual courses, were at too high a level to be intrinsically meaningful for academic decision makers. Moreover, tests of the model’s ability to predict the effects of changing enrollments yielded disappointing results. (Errors of up to forty percent were not uncommon.) Efforts to develop the early generations of “activity-based costing” (ABC) models in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s ran into the same problems. In the end, it became apparent that academic acceptance and forecast accuracy required modeling to be done at the level of individual courses.

How Course-Based Models Add Value to Academic Decision Making

The consequences of budget-makers’ inability to penetrate the fine structure of departmental teaching activity is reflected in a conversation I had during my year as Stanford’s Acting Provost. I had asked an influential school dean whether certain courses might be more of a financial drain than was worthwhile given their contributions to the school’s mission. I soon learned that the dean had no knowledge or interest in this question. Instead, I got a lecture about the “real job” of a dean: “to persuade the provost to supply as much money as possible and then stand back and let the school and its departments spend it as they pleased.” (No wonder university costs seem to rise inexorably.) Conversations about the economics of teaching were impossible because neither of us had any meaningful data on the subject or even a conceptual framework for asking good questions. Any of today’s academic resourcing models would have enabled me to begin a dialogue which, in time, might have expanded the dean’s perspective. Without a model, I had no foundation for such a conversation.

The need for course-based models continued to bug me, and some twenty years later I joined with professor Bob Zemsky of the University of Pennsylvania to facilitate a workshop on how to build them. (The workshop was sponsored by EDUCOM, on whose board I had served, which was a predecessor organization to EDUCAUSE.) The workshop formulated a teaching activity framework that is essentially the one used in today’s advanced academic resourcing models. The framework is described in my Honoring the Trust: Quality and Cost Containment in Higher Education.

I pursued these ideas sporadically for the next decade or so. Then, circa 2010, a grant from the Lumina Foundation allowed me to develop and field test the prototype course-level model described in chapter 4 of Reengineering the University. That work spawned additional research on the best ways to construct course-level models and the ways they can most easily be implemented and used by institutions.

It’s now eminently practical to model teaching activity at the course level. My recent blog about course-level models as game changers described the models briefly and my forthcoming book does so more extensively. Once a course-level model has been constructed, it is relatively straightforward to link it with models in the outer ring of Figure 1. For the first time, colleges and universities can get the data they need for evidence-based holistic conversations about academic resourcing.

Will you be at the ACE annual meeting in San Diego? If so, I’d love to meet you. Gray and I are co-presenting Academic Program Management: Making Data-Driven Decisions. The session meets March 16th at 1:45pm. Please come introduce yourself!