The rise of artificial intelligence presents higher education with all kinds of opportunities in areas from teaching and learning to finance. However, this powerful engine is entirely dependent on the fuel it’s given: data. If that data is flawed, the resulting AI-driven information will inevitably be distorted, potentially leading institutions down misguided and costly paths.

AI offers valuable applications in higher education, such as providing immediate answers to decision-makers’ questions about extensive academic program datasets. Through a natural language interface, AI agents allow users to query these vast datasets and receive instant numerical or textual responses. However, for academic program evaluation, the AI is only helpful if the data it uses is accurate.

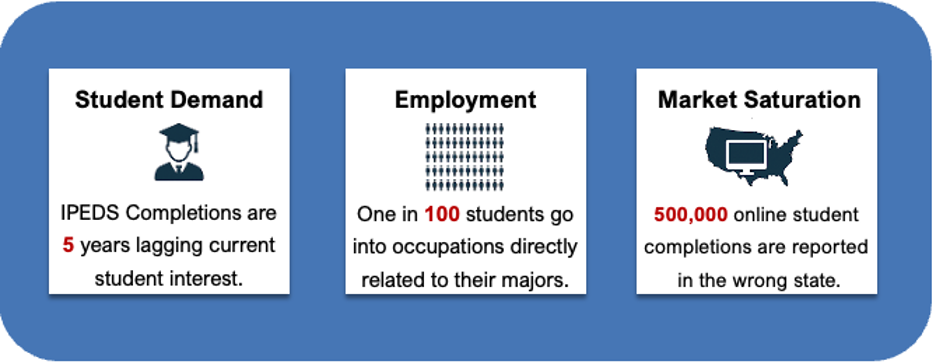

The Hidden Costs of Outdated Data: 5, 100, and 500,000 Reasons to Worry

Higher education data providers usually ignore three notable errors. Gray DI corrects these errors as a fundamental tenet of our Program Evaluation System (PES) Markets tool. These errors are represented by the following:

Student demand data for academic programs can be effectively 5 years out of date.

Career pathway analyses might only reflect one out of every 100 actual occupations graduates go into.

In the booming online education sector, nearly 500,000 students are reported to IPEDS in the wrong market.

These errors have profound consequences, and feeding any AI tool inaccurate data could be harmful for students, administrators, and employers.

Beyond IPEDS: Capturing Real-Time Student Demand

The challenge of outdated information plagues evaluations of student demand when relying solely on Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) completions data. Typically, IPEDS data is released with a two-year lag; as of June 2025, the most current data available is through June 2023. Furthermore, completions data reflects student aspirations from around two to five years prior – when they initially chose their major. Therefore, 2023 completion figures mirror student demand from the 2018-2020 period, making it significantly out of sync with current market trends. While invaluable for historical analysis, IPEDS completions data alone lacks the immediacy needed to capture recent shifts in student demand for academic programs.

To gain a more comprehensive and accurate understanding, triangulating data sources is crucial. For instance, Google keyword searches for academic programs offer a forward-looking indicator of student demand, revealing what prospective students are actively researching in real-time. This data, often updated monthly, provides a lens into emerging trends. One drawback is that search volume indicates interest, not necessarily the intent or qualification to enroll, but it provides a crucial early signal. Similarly, up-to-date student enrollment data, like that from the National Student Clearinghouse (updated three times a year), offers a current snapshot of the student landscape, tracking enrollment volume and growth rates locally and nationally. However, this program-level data may not capture undeclared students.

Beyond the Crosswalk: Uncovering True Graduate Career Paths

Traditional labor market data, a cornerstone of program planning, has limitations. Standard crosswalks linking academic majors to specific occupations often present a narrow, and even discouraging, view of career pathways (especially in the liberal and fine arts). Typical crosswalks may only show one occupation for every 100 occupations graduates go on to enter. For example, the National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) program-to-occupation crosswalk lists “postsecondary teachers in philosophy or religious studies” as the only possible occupation for philosophy graduates. However, real-world alumni data paints a far richer and more diverse picture. An analysis of over 70,000 philosophy alumni profiles reveals that postsecondary teaching constitutes only about one percent of graduate career paths. Instead, top occupations include roles in sales, marketing, project management, advertising, law, and software development, highlighting a significant disconnect between traditional crosswalks and real-world career outcomes. Alumni data by major, school, and location is a much richer dataset to evaluate employment opportunities for graduates.

Market Saturation

One of the most significant areas impacted by flawed data is the evaluation of online competition. Many institutions rely on IPEDS to gauge the national online education outlook. While IPEDS provides a wealth of information, its methodology for reporting online completions introduces a critical blind spot. Online completions are attributed to an institution’s headquarters location, regardless of where the student actually resides and studies. Take Arizona, for example, home to several major national online universities such as Arizona State University, the University of Arizona, University of Phoenix, Grand Canyon University, and Northern Arizona University. In 2023, 83 percent of the online degrees conferred by these five institutions were awarded to students living outside of Arizona.

This reporting anomaly fundamentally taints any analysis of local or even regional competition. In a market like Phoenix, the competitive landscape for online programs appears vastly overstated because completions from students across the nation are attributed to institutions headquartered there. Conversely, in other markets, the true extent of online competition is significantly understated, masking the reality of local students enrolling in programs offered by institutions in other states.

The consequences extend beyond competitive analysis, distorting labor market evaluations. Phoenix might erroneously appear to have an oversupply of graduates in certain fields, while other markets could incorrectly signal shortages. This leads to misinformed decisions about program development and resource allocation. In 2023 alone, out of 1,240,710 total US online completions, over 530K – a substantial 43 percent – were earned by students residing outside the reporting institution’s state, yet all were incorrectly attributed to the institution’s home state. More nuanced data sources, such as those leveraging National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (NC SARA) data coupled with proprietary algorithms, are essential to localize online students to their home markets, providing a far more accurate picture of competitive dynamics and labor market supply.

In conclusion, as higher education increasingly embraces the formidable power of AI for student success and strategic decision-making, the imperative for clean, accurate, and timely data is paramount. Relying on flawed, incomplete, or outdated information can lead to a distorted understanding of student demand, the competitive landscape, and labor market realities, resulting in misallocated resources and missed opportunities. By moving beyond the limitations of single, traditional datasets and instead leveraging multiple, robust data sources – including current enrollment figures, forward-looking indicators of student interest, and more granular competitive and employment intelligence – institutions can unlock the true potential of AI.