Many community colleges and other higher education institutions use labor market forecasts to inform decisions on academic programs, faculty hiring, and facilities investments. In particular, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) forecast growth rates are often used to identify potential new programs and those that merit further investment. How accurate are these forecasts?

When BLS Becomes BS

To answer this question, we started with the BLS 2012 forecasts by Standard Occupation Code (SOC). These forecasts estimated growth rates and total employment for 2022 in approximately 850 SOCs. We used the BLS rates to estimate employment from 2012 to 2019, ending before the pandemic. This was a period of slow, stable growth, with no major terrorist attacks, pandemics, or recessions; this stability should have made predictions, including the BLS forecasts, more accurate.

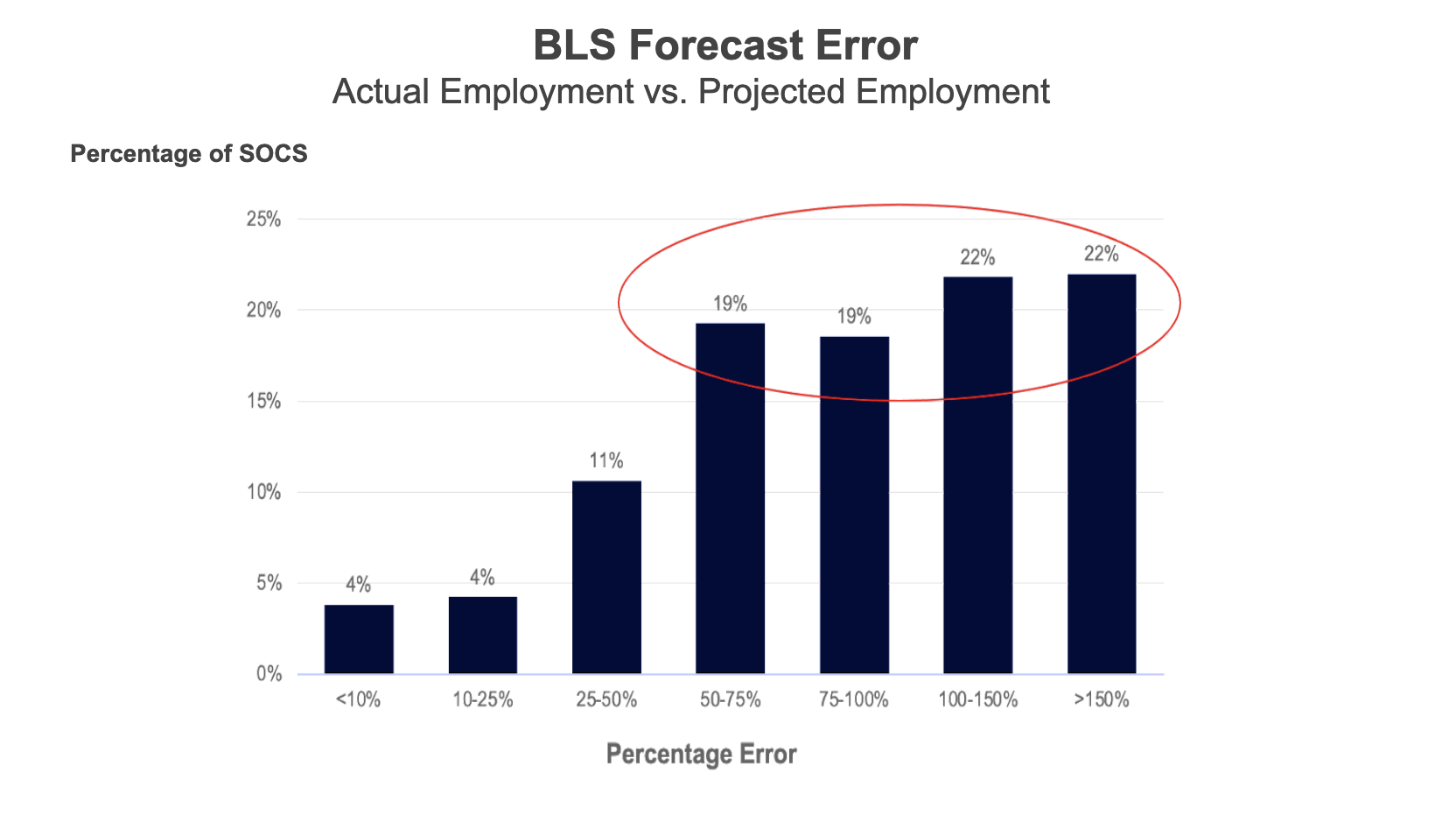

As illustrated below, only 8% of the BLS forecast growth rates were roughly right, that is, within 25% of the actual growth rate. 82% of the forecasts were off by 50% or more.

To be fair, the analysis did not show that BLS estimates of the number of employees in an occupation were off by 50% or more. Let’s work through an illustration: In a SOC with 1.0 million people employed, let’s assume that BLS forecast 2% growth and that the actual growth rate was 0%. At a 2% forecast growth rate, 2019 employment would be 1.15 million, and actual employment would remain at 1.0 million (at 0% growth). While the percentage growth rate was off by 100% (2% vs. 0%), the predicted number of people employed differs only by 0.15 million or 15%.

The Dismal Science Problem

As I mentioned in my last blog, we should not blame the BLS for forecasting errors. They have recently updated their forecasting methodology, and it may be better than it was – but we won’t know for ten years. State forecasts are likely to be more error-prone since the national data smooths out more volatile state-level data (think oil booms and busts in Oklahoma). In any case, I believe the U.S. economy is both complex and chaotic; it is impossible to make accurate 10-year forecasts, even in normal times, like the period from 2012 to 2019. When we add in unpredictable events like wars, terrorist attacks, recessions, and pandemics, our vision of the future becomes cloudy indeed.

Making Accurate Predictions

That said, I think some areas will be more predictable than others, but I have not tested this hypothesis. For example, demographic trends are relatively predictable. The number of people who will be 60 in 20 years can be predicted with reasonable accuracy since we know how many people are now 40. As a result, fields like healthcare that are linked to an aging population are likely to be more predictable over the long term. However, even these fields may suffer enormous disruptions, like the pandemic, that belie the forecasts.

How is a community college, or any other higher education institution, supposed to make long-term investments in growing fields if growth rates are so uncertain? Please stay tuned. I’ll get to that soon.