When colleges and universities are financially stressed, one consideration is to cut academic programs in the hopes of balancing the budget. Program cuts have been widely reported – but are they actually a good idea? Are the cost savings enough to offset potential enrollment and revenue declines?

To understand how cutting a program will impact your financial health, you need to understand the economics of your academic portfolio and the cost of delivering your programs, the revenue they generate, and the margins they produce. Let’s take a look at an illustrative example using data from Gray DI’s PES Economics & Outcomes platform.

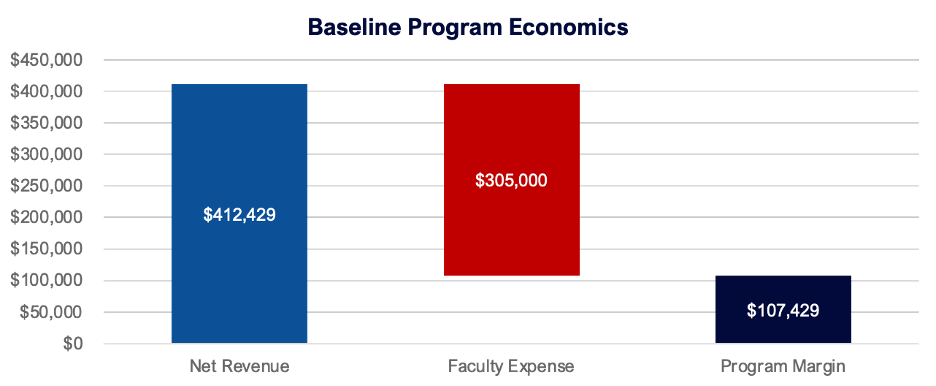

Baseline Program Economics

In this example, the program under consideration has three faculty FTE dedicated to teaching courses for the major. There are 22 students enrolled, and six new students enroll each year. Even though the program is small, it generates $412k in annual net revenue and costs $305k to deliver, thus producing a contribution margin of $107k.

On the surface, this program may seem like an easy target to cut—it is small in terms of enrollment, faculty FTE, and contribution margin—but digging a little deeper reveals that the decision may not be so simple. Even if the school decides to cut the program, it will need to be taught out over the next few years.

On the surface, this program may seem like an easy target to cut—it is small in terms of enrollment, faculty FTE, and contribution margin—but digging a little deeper reveals that the decision may not be so simple. Even if the school decides to cut the program, it will need to be taught out over the next few years.

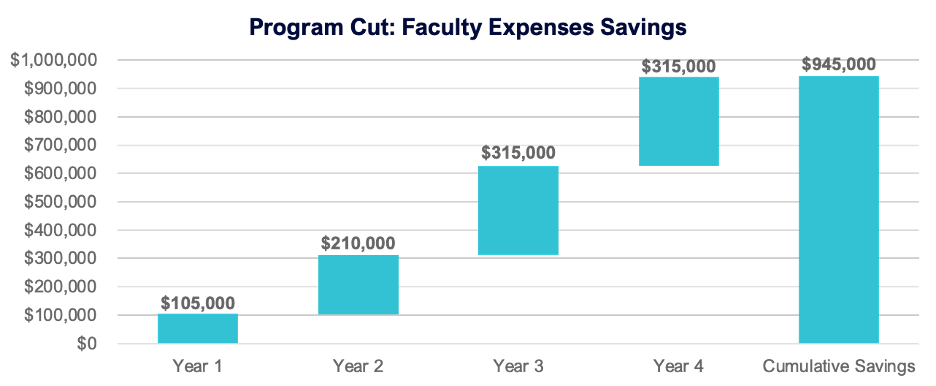

Potential Savings by Cutting a Program

Let’s look at how much the school can expect to save by cutting the program.

In the first year of teaching out the program, the school still needs two faculty FTE to teach its courses to existing students. This is a reduction of 1 FTE, or $105k. In year two of the teachout, only 1.0 faculty FTE is required, so the savings increase to $210k. In year three and afterward, no more faculty are required and the annual saving is $315k. The cumulative savings after the teachout are $945k.

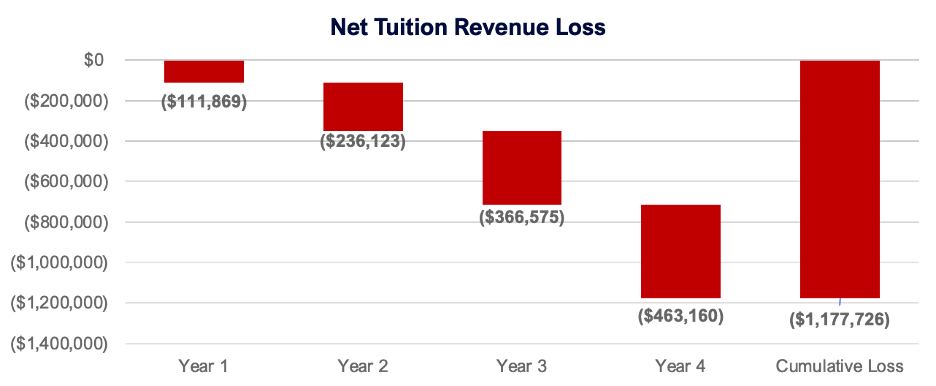

Now let’s look at the revenue side. For direct variable economics, we are only considering net revenue from tuition and fees from students enrolled in the program and excluding any other revenue sources (e.g., room and board).

Revenue Scenarios When Cutting a Program

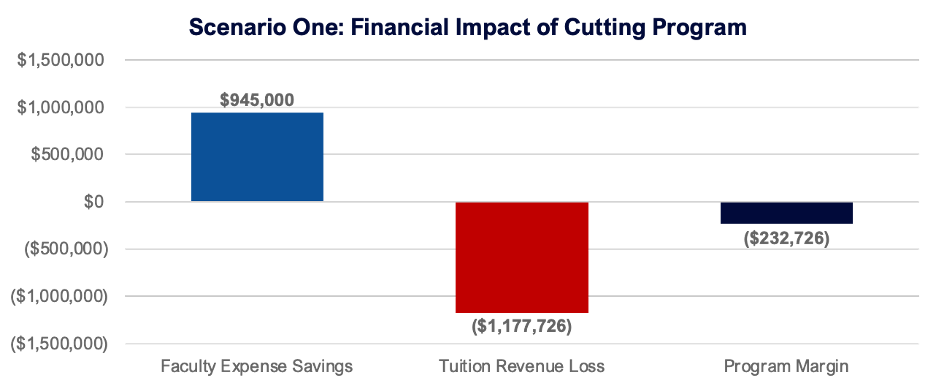

Scenario One: All New Students Are Lost

In the most extreme scenario, students enroll in the university specifically for this program; without this program, the school loses all of these students. As the program is taught out, fewer students remain in the major each subsequent year, and net revenue declines to $0. By the end of the teachout, the cumulative revenue loss is $1.18 million.

In this scenario, the loss of tuition revenue is greater than the cumulative cost savings. Cutting this program makes the school’s financial situation worse, not better.

Scenario Two: Some Students Are Retained

Scenario Two: Some Students Are Retained

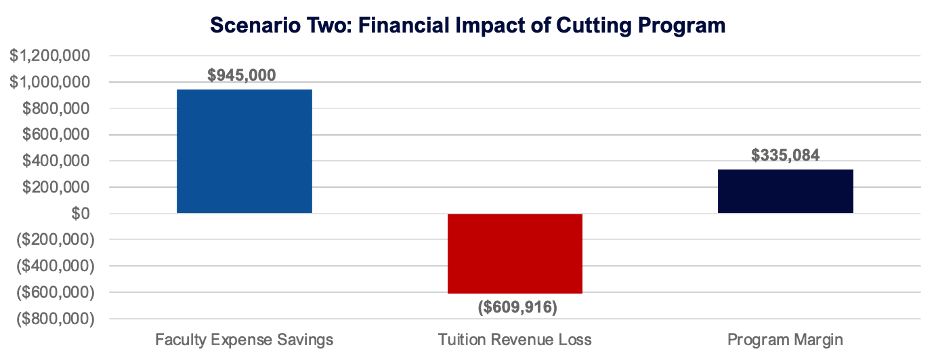

In a less extreme scenario, some students will still choose to enroll in the university despite the program being cut: they will simply choose another major. The critical question is – how many students do you need to keep each year to make the financial impact of cutting the program a net positive?

Going back to our example, the program historically has six new enrollments per year. If the school can maintain enrolling three of the six new enrollments in subsequent years, cutting the program will end up about breakeven. Despite the considerable effort involved in phasing out the program, the financial outcome is ultimately neutral, with no significant net gain or loss.

While we have illuminated the risk of making program cuts without a data-informed process, we have also simplified the ramifications for the sake of the argument. For instance, we assumed that the incremental new students that were retained in scenario two are associated with $0 of incremental cost: that is, they are filling empty seats in courses that are already being taught. As soon as these incremental new students push course capacities over the limit and require additional sections to be taught, these new students are no longer “free.” Another detail we trivialized was letting go of three full-time faculty members. This can be a tense and emotional process and can bring down the morale of an institution. It can require collective bargaining agreements, severance packages, or early retirement incentives – processes that take a considerable amount of time and effort to put into place, not to mention additional costs.

While we have illuminated the risk of making program cuts without a data-informed process, we have also simplified the ramifications for the sake of the argument. For instance, we assumed that the incremental new students that were retained in scenario two are associated with $0 of incremental cost: that is, they are filling empty seats in courses that are already being taught. As soon as these incremental new students push course capacities over the limit and require additional sections to be taught, these new students are no longer “free.” Another detail we trivialized was letting go of three full-time faculty members. This can be a tense and emotional process and can bring down the morale of an institution. It can require collective bargaining agreements, severance packages, or early retirement incentives – processes that take a considerable amount of time and effort to put into place, not to mention additional costs.

Cutting academic programs can seem like a quick fix for budget woes, but it’s a complex decision with far-reaching consequences. Before making any cuts, it’s crucial to evaluate program economics: the revenue, costs, and contribution margin associated with teaching a program. By using tools like Gray DI’s PES Economics & Outcomes, institutions gain a comprehensive understanding of their programs to make data-informed decisions that support long-term financial sustainability.